33 and 79- Hayyam’s Calendar

In the 11th century, Central Asia had become a cradle that gave birth to great figures who profoundly influenced the Islamic world. The scientific spark that ignited in Baghdad soon reached these lands, which were also the birthplace of paper. Muslims, driven by a great intellectual appetite, translated the works of Ancient Greek philosophers into Arabic and, by reinforcing geometric thinking, developed an instrument they called the astrolabe.

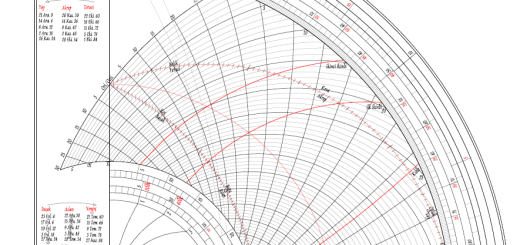

Although this instrument had practical applications in cartography, geography, and navigation, its place in Islamic thought went far beyond being a mere scientific tool. The astrolabe offered a schematic explanation of celestial motions and the synchronization of their interrelationships. Essentially, the astrolabe consisted of reading the movements occurring in the universe through geometry.

In the early period, Muslims referred to geometry as cumetriya, but later the term hendese, derived from the Persian word endāze meaning “measurement,” became preferred. The astrolabe was a device that reflected the vast horizons of human reason, for it revealed, through intellect, things that could not be directly observed, and demonstrated—within a process lasting only seconds—solutions to problems that could not be resolved even across hundreds of pages of calculations.

In the world of the Sumerians, who based timekeeping on the Moon, the number 365 was inconvenient due to its poor factorization, so it was rounded to 360, which was accepted as a full angle. One of the divisors of 360, the number 60, was chosen as the base of the numerical system. Thanks to this system, the cycles of celestial bodies could be easily calculated and converted into one another.

The Hebrews, on the other hand, used a mixed calendar system based on both the Moon and the Sun, adding an extra month in certain years to reconcile the lunar and solar calendars within a 19-year cycle. The Prophet of Islam, Muhammad (peace be upon him), prohibited this practice by divine command, because in pre-Islamic society it was used to circumvent the rule forbidding warfare during the sacred months. Muslims determined their holy days according to the lunar calendar, but prayer times were determined by the Sun. Therefore, in order to create fixed and non-slipping prayer timetables, an accurate solar calendar was required.

Calendar studies became a central interest of great figures regarded as pioneers of Islamic science, such as al-Khwarizmi, al-Biruni, and Ulugh Beg. Muslims were familiar with the Alexandrian calendar used by the Greeks. However, having realized that this calendar was flawed and subject to drift, they placed conversion tables on the reverse side of astrolabes to convert the Alexandrian calendar into the Zodiac (astrological) calendar. Since the drift of the Julian calendar differed each year, astrolabes produced in different periods yielded different calculations.

Sciences developed along the axis of geometry were used as tools to uncover the mathematical order inherent in the universe. The divine aspect of geometric constants such as pi had also attracted the attention of Ancient Greeks, because the value of such constants was believed to be determined by God. Discovering a geometric constant thus meant uncovering one of God’s secrets. Muslims established observatories in Baghdad, Samarkand, and Isfahan, and pursued these divine mysteries.

Meanwhile, alphabetic numeral systems that were already widespread in the Mediterranean before Islam led Muslims to develop their own system known as abjad (ebced) numerology. According to this system, every word written in Arabic letters could be converted into a numerical value. This method formed a bridge between the verbal and numerical worlds. Similarly, the astrolabe converted dates and hours into angular values, once again transforming time into numerical form. The ability to translate verbal, spatial, and temporal worlds into a numerical foundation made it possible to compare the harmony of these numbers with one another.

Omar Khayyam emerged as a brilliant scholar during the height of the Great Seljuk Empire. The Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk recognized his talent and appointed him as chief astronomer of the Isfahan Observatory. Khayyam was highly skilled in computational science, proposed original theorems, opened new paths in analytic geometry, and wrote works that very few others could fully comprehend. Khayyam was tasked with preparing a solar calendar. Together with his team in Isfahan, he conducted extremely precise observations, measuring and recording the Sun’s annual motion with second-level accuracy. He then transformed these observations into practical mathematical results. According to modern high-precision measurements, a year consists of 365.2422 days.

When calculating the leap-year rule in calendar science, we search for a fraction that yields the decimal part—that is, a fraction that equals 0.2422. If such a fraction is found, a leap-year rule can be constructed accordingly.

However, we encounter an inconvenient fraction such as 1211/5000, which would require tracking a 5000-year cycle—an almost unsolvable algorithm. Therefore, a fraction very close to 0.2422, yet simple and practical, was required. This was undoubtedly a problem at which Khayyam himself must have been stuck. He needed to find a fraction that approximated this value while remaining computationally practical.

At this point, it is highly likely that Khayyam resorted to Cifr, a field regarded as a branch of mathematics. In the Qur’an, the repetition counts of certain words have been found meaningfully coincidental (tawāfuq), and the number of times many words appear has been studied. For example, the word day (yawm) appears 365 times, days appears 30 times, and month (shahr) appears 12 times.

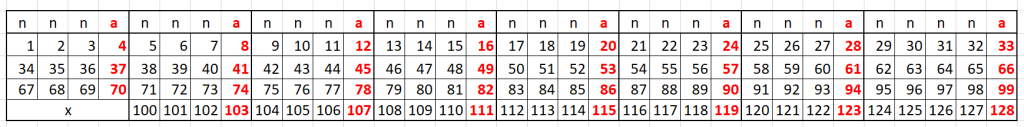

The word Sun appears 33 times across 32 verses. What could the number 33 have to do with the Sun? Khayyam’s mathematical genius revealed a system that may seem simple to many of us today, yet is extremely sophisticated. Like the Julian calendar, Khayyam applied a leap year every four years to correct the six-hour surplus of the 365-day year. However, in the 32nd year he changed the rule and postponed the leap year to the 33rd year. Thus, in Khayyam’s calendar, the leap years in the first 33 years were:

4 – 8 – 12 – 16 – 20 – 24 – 28 – 33

In this way, there were 8 leap years in 33 years. The fraction 8/33 yields 0.2424, which is extremely close to 0.2422 and is also remarkably simple and practical. Khayyam thus discovered that the ideal number of the solar system was 33.

Khayyam’s work would later influence Pope Gregory XIII, who attempted to rival Khayyam five centuries later. Gregory’s calculations did not even come close to Khayyam’s accuracy. His calendar defined the year as 365.2425 days and exhibited micro-shifts at the beginnings and ends of centuries, resulting in a poorly tuned system.

Pope Gregory introduced a 100-year cycle and an upper 400-year cycle into the calendar. Only by using these two cycles was he able to produce a calendar that would not drift for 3000 years. If we add an upper cycle to Khayyam’s 33-based calendar, however, the result is breathtaking in its accuracy: it does not drift for a million years.

To summarize in a single sentence: after completing three cycles of Khayyam’s 33-year algorithm, in the fourth cycle it suffices to skip the first four terms. When applied in this way, we obtain 31 leap years distributed homogeneously over 128 years.

31/128 = 0.2421875, which differs from the astronomically measured value of 365.24218967 only in the millionths place—meaning a drift of merely one day per million years. Only 5 split seconds error margin per year.

If such a magnificent solar calendar was devised by Khayyam, what kind of structure would emerge if the same method were applied to a lunar calendar? What would be the Moon’s ideal number? The answer once again leads to a surprising result that confirms Khayyam’s system.

A lunar year consists of 354.3670 days, requiring a fraction that yields 0.3670. Practical fractions close to this value can now be found rapidly using artificial intelligence. One such fraction is 11/30 (0.3666), accepted by many calendar converters. Although close and convenient, distributing 11 leap years within 30 years is difficult, prompting a search for a more suitable number. A more accurate and practical fraction that does not involve large numbers is 29/79.

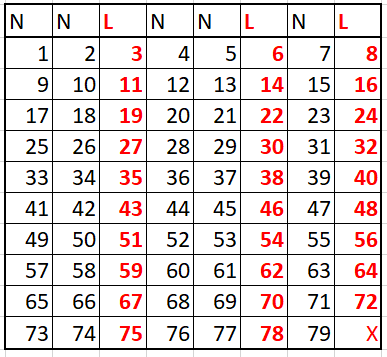

This requires a 79-year cycle containing 29 leap years. A normal lunar year has 354 days, and a leap year has 355 days. In a 79-year cycle consisting of 50 normal years and 29 leap years, a perfectly accurate lunar calendar that does not drift for 100,000 years can be constructed. These leap years can be distributed homogeneously as shown below.

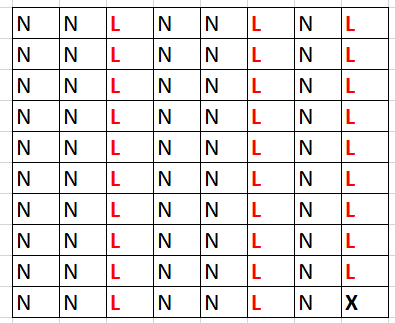

Thus, the leap-year algorithm takes the following form (L: leap year, N: normal year):

A nearly fully harmonic calendar algorithm becomes possible, making it more convenient than a 30-year system.

Expressed as a simple eight-term numerical sequence, this algorithm consists of repeating the sequence

“N N L N N L N L” infinitely and omitting terms that are multiples of 80.

Does the ideal lunar number, 79, correspond to any number in the Qur’an? Since this calendar is calculated by comparing a lunar year to a solar day, we must consider the words Moon and Sun together:

Moon: 27

Sun: 33

Moon and Sun together: 19

27 + 33 + 19 = 79

İbrahim Aybek

4th Delve, 1404

Lisbon

Son yorumlar